For many years, Wireless Waffle has enjoyed the occasional bout of FM DXing. That is to say that when the propagation conditions have permitted, time has been enjoyably spent tuning up and down the FM band to see what can be heard.

For many years, Wireless Waffle has enjoyed the occasional bout of FM DXing. That is to say that when the propagation conditions have permitted, time has been enjoyably spent tuning up and down the FM band to see what can be heard.The logbook of this anomalous reception has been sitting waiting to be published for ages and now, with a quiet weekend with not much else to do has presented itself, it's finally morphed into a web-page of it's own.

Wireless Waffle is therefore proud to announce the FM DX Logbook. If this means nothing to you, then don't take a look. Even if it does, just one look is all it takes, as someone wiser and more lyrical once suggested.

add comment

( 1608 views )

| permalink

|

( 3 / 30460 )

( 3 / 30460 )

( 3 / 30460 )

( 3 / 30460 )

So many organisations and individuals involved in telecommunications continue to use the term 'exponential' to describe the growth in internet traffic, whether carried on fixed networks, or on wireless. Reports such as the ITU.M... forecast continued exponential growth until 2030 and there are numerous publications that cite growth following an exponential curve. But (with the possible expansion of the universe), nothing grows forever, let alone exponentially.

Let's consider the implications of exponential growth in internet data traffic. According to various sources, the amount of data transferred over the internet in 2018 will reach 1 Zettabyte (or 8x10²¹ bits). If growth continues exponentially at current rates (e.g. around a 50% year-on-year increase), the following things will happen: This is to say nothing of the electrical power requirements. Based on current future expectations of the energy required to transfer a bit of data (around 1 picoJoule per bit), by around 2080 we would need every single Watt of power generated on the planet Earth today to keep the Internet's lights on (let alone the problems of the sizes of batteries that would be needed in mobile devices). By 2113, we would need to capture every milliWatt of power that the Sun emits in order to power the Internet (in essence building a Dyson sphere). Slowly but surely the exponential growth in Internet traffic would begin to consume the whole universe.

This is to say nothing of the electrical power requirements. Based on current future expectations of the energy required to transfer a bit of data (around 1 picoJoule per bit), by around 2080 we would need every single Watt of power generated on the planet Earth today to keep the Internet's lights on (let alone the problems of the sizes of batteries that would be needed in mobile devices). By 2113, we would need to capture every milliWatt of power that the Sun emits in order to power the Internet (in essence building a Dyson sphere). Slowly but surely the exponential growth in Internet traffic would begin to consume the whole universe.

It is therefore to be hoped that the universe is actually infinite and continues to expand (though opinions on this are divided), otherwise it will run out of power before our insatiable demand for watching cat videos is finally sated.

You might wonder what all this has got to do with radio spectrum, as there's always a Wireless Waffle angle on that topic. The simple fact is that although all the energy on the planet may be consumed keeping the Internet going, the amount of radio spectrum required to deliver the speed of connection necessary to transfer that much data will consume all available frequencies far before 2080. This is, of course, the desired goal of the mobile industry!

You might wonder what all this has got to do with radio spectrum, as there's always a Wireless Waffle angle on that topic. The simple fact is that although all the energy on the planet may be consumed keeping the Internet going, the amount of radio spectrum required to deliver the speed of connection necessary to transfer that much data will consume all available frequencies far before 2080. This is, of course, the desired goal of the mobile industry!

As Professor Albert Bartlett of the University of Colorado so aptly puts it:

Let's consider the implications of exponential growth in internet data traffic. According to various sources, the amount of data transferred over the internet in 2018 will reach 1 Zettabyte (or 8x10²¹ bits). If growth continues exponentially at current rates (e.g. around a 50% year-on-year increase), the following things will happen:

By 2161, the number of bits of data transferred across the internet will equal the number of atoms in a human body.

By 2161, the number of bits of data transferred across the internet will equal the number of atoms in a human body.- By 2229, the number of bits of data transferred across the internet will equal the number of atoms in the planet Earth.

- By 2270, the number of bits of data transferred across the internet will equal the number of atoms in the Solar system.

- By 2329, the number of bits of data transferred across the internet will equal the number of atoms in the Milky Way galaxy (excluding dark matter).

This is to say nothing of the electrical power requirements. Based on current future expectations of the energy required to transfer a bit of data (around 1 picoJoule per bit), by around 2080 we would need every single Watt of power generated on the planet Earth today to keep the Internet's lights on (let alone the problems of the sizes of batteries that would be needed in mobile devices). By 2113, we would need to capture every milliWatt of power that the Sun emits in order to power the Internet (in essence building a Dyson sphere). Slowly but surely the exponential growth in Internet traffic would begin to consume the whole universe.

This is to say nothing of the electrical power requirements. Based on current future expectations of the energy required to transfer a bit of data (around 1 picoJoule per bit), by around 2080 we would need every single Watt of power generated on the planet Earth today to keep the Internet's lights on (let alone the problems of the sizes of batteries that would be needed in mobile devices). By 2113, we would need to capture every milliWatt of power that the Sun emits in order to power the Internet (in essence building a Dyson sphere). Slowly but surely the exponential growth in Internet traffic would begin to consume the whole universe. It is therefore to be hoped that the universe is actually infinite and continues to expand (though opinions on this are divided), otherwise it will run out of power before our insatiable demand for watching cat videos is finally sated.

You might wonder what all this has got to do with radio spectrum, as there's always a Wireless Waffle angle on that topic. The simple fact is that although all the energy on the planet may be consumed keeping the Internet going, the amount of radio spectrum required to deliver the speed of connection necessary to transfer that much data will consume all available frequencies far before 2080. This is, of course, the desired goal of the mobile industry!

You might wonder what all this has got to do with radio spectrum, as there's always a Wireless Waffle angle on that topic. The simple fact is that although all the energy on the planet may be consumed keeping the Internet going, the amount of radio spectrum required to deliver the speed of connection necessary to transfer that much data will consume all available frequencies far before 2080. This is, of course, the desired goal of the mobile industry!As Professor Albert Bartlett of the University of Colorado so aptly puts it:

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.

Since his election as President of the United States, one of Donald Trump's key programmes has been the construction of a wall along the border with Mexico. Many people believe that the purpose of such a wall is to reduce illegal immigration along the border and to stop goods being illegally transported between the two countries without clearing the necessary customs.

Wireless Waffle has discovered, however, that the reason for the construction of the wall is nothing to do with immigration or customs but is needed to prevent transmissions from mobile base stations using the 700 MHz band in Mexico from interfering with mobile base stations in the 700 MHz band in the USA.

Wireless Waffle has discovered, however, that the reason for the construction of the wall is nothing to do with immigration or customs but is needed to prevent transmissions from mobile base stations using the 700 MHz band in Mexico from interfering with mobile base stations in the 700 MHz band in the USA.

It is often said that radio signals do not respect international borders: signals from one country do not abruptly stop when they reach an arbitrary line on a map. As such, signals from mobile base stations in border areas are prone to cause interference to base stations on the opposite side of the border. Several European countries have reached an agreement (known as the HCM Agreement) which defines how much cross-border 'overspill' is permitted.

In general when signals cross borders, the use of the radio spectrum either side of the border is similar, that is to say that if the frequencies are used on one side for base station transmissions, it will be used on the other side for the same purpose. For example, if the signals from one country's mobile base stations are roughly the same strength along the border as those from its neighbour, and assuming that a mobile handset will latch onto the strongest signal, as it passes from one country to the next, it will automatically select the network for the country in which it is located.

The worst case situation is where the transmitters on one side of the border (the 'downlink') which are typically 1000 Watts or more for a mobile base station are on the same frequencies as the receivers on the other (the 'uplink') which are trying to receive signals from mobile handsets with 1 Watt of power who are several miles away. This is akin to having someone in one country shouting directly into the ear of someone standing next to them who is simulatneously trying to hear one of their own residents whispering to them from a great distance. No manner of technological development will solve this problem and hence neighbouring countries try and avoid this happening.

The worst case situation is where the transmitters on one side of the border (the 'downlink') which are typically 1000 Watts or more for a mobile base station are on the same frequencies as the receivers on the other (the 'uplink') which are trying to receive signals from mobile handsets with 1 Watt of power who are several miles away. This is akin to having someone in one country shouting directly into the ear of someone standing next to them who is simulatneously trying to hear one of their own residents whispering to them from a great distance. No manner of technological development will solve this problem and hence neighbouring countries try and avoid this happening.

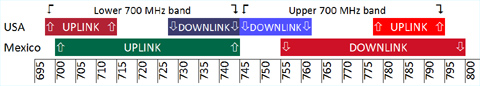

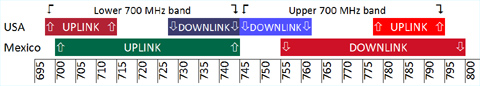

Between the US and Mexico in the 700 MHz band, however, this situation arises. The diagram below shows how the frequencies in this mobile band are used in either country. A downlink (mobile base station transmission) on the same frequency as an uplink (mobile base station receive) will cause exactly the kind of problems identified above.

So... the base stations in the 'lower 700 MHz band' in the USA will cause immense interference to the base stations in Mexico operating at the upper end of the Mexican 700 MHz band, and the base stations in Mexico will cause immense interference to the 'upper 700 MHz band' base stations in the USA.

There is no straightforward solution to this problem, other than one or other country adopting the same frequency plan as its neighbour. As both countries already have services operating in the bands, this is beyond unlikely. The only way to overcome such a problem is therefore to try and stop signals from one side of the border reaching the other side. The laws of physics dictate that the only way to do this is to build a barrier that is impervious to radio signals, such as, for example, a tall metallic wall (or one with metal running up the inside). Metal boxes known as Faraday cages are used in laboratories (and sci-fi movies) to perform just this task.

There is no straightforward solution to this problem, other than one or other country adopting the same frequency plan as its neighbour. As both countries already have services operating in the bands, this is beyond unlikely. The only way to overcome such a problem is therefore to try and stop signals from one side of the border reaching the other side. The laws of physics dictate that the only way to do this is to build a barrier that is impervious to radio signals, such as, for example, a tall metallic wall (or one with metal running up the inside). Metal boxes known as Faraday cages are used in laboratories (and sci-fi movies) to perform just this task.

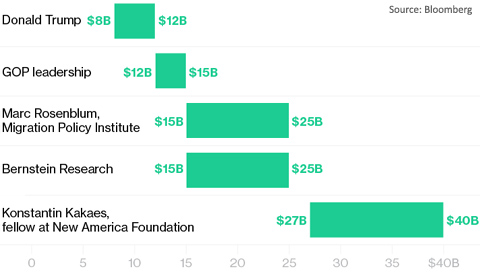

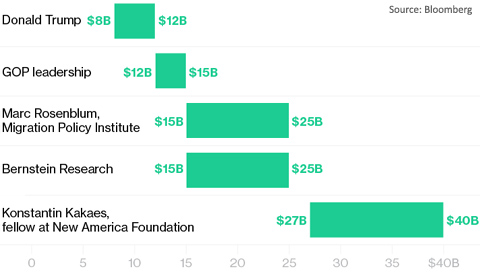

The 700 MHz band was sold at auction in the USA for US$19 billion in 2008. Estimates of the cost of the wall vary, but the mean value is around US$20 billion. This is no co-incidence. Having paid US$19 billion for the spectrum in the 700 MHz band, the US operators have a reasonable expectation that they can use the frequencies without undue interference and thus a 'Faraday Wall' is necessary. As long as Mr Trump can build it for less than US$19 billion, the operators will be happy, and the Federal Reserve will still have made a small profit on the sale of the spectrum. Win-win as they say.

Wireless Waffle has discovered, however, that the reason for the construction of the wall is nothing to do with immigration or customs but is needed to prevent transmissions from mobile base stations using the 700 MHz band in Mexico from interfering with mobile base stations in the 700 MHz band in the USA.

Wireless Waffle has discovered, however, that the reason for the construction of the wall is nothing to do with immigration or customs but is needed to prevent transmissions from mobile base stations using the 700 MHz band in Mexico from interfering with mobile base stations in the 700 MHz band in the USA.It is often said that radio signals do not respect international borders: signals from one country do not abruptly stop when they reach an arbitrary line on a map. As such, signals from mobile base stations in border areas are prone to cause interference to base stations on the opposite side of the border. Several European countries have reached an agreement (known as the HCM Agreement) which defines how much cross-border 'overspill' is permitted.

In general when signals cross borders, the use of the radio spectrum either side of the border is similar, that is to say that if the frequencies are used on one side for base station transmissions, it will be used on the other side for the same purpose. For example, if the signals from one country's mobile base stations are roughly the same strength along the border as those from its neighbour, and assuming that a mobile handset will latch onto the strongest signal, as it passes from one country to the next, it will automatically select the network for the country in which it is located.

The worst case situation is where the transmitters on one side of the border (the 'downlink') which are typically 1000 Watts or more for a mobile base station are on the same frequencies as the receivers on the other (the 'uplink') which are trying to receive signals from mobile handsets with 1 Watt of power who are several miles away. This is akin to having someone in one country shouting directly into the ear of someone standing next to them who is simulatneously trying to hear one of their own residents whispering to them from a great distance. No manner of technological development will solve this problem and hence neighbouring countries try and avoid this happening.

The worst case situation is where the transmitters on one side of the border (the 'downlink') which are typically 1000 Watts or more for a mobile base station are on the same frequencies as the receivers on the other (the 'uplink') which are trying to receive signals from mobile handsets with 1 Watt of power who are several miles away. This is akin to having someone in one country shouting directly into the ear of someone standing next to them who is simulatneously trying to hear one of their own residents whispering to them from a great distance. No manner of technological development will solve this problem and hence neighbouring countries try and avoid this happening. Between the US and Mexico in the 700 MHz band, however, this situation arises. The diagram below shows how the frequencies in this mobile band are used in either country. A downlink (mobile base station transmission) on the same frequency as an uplink (mobile base station receive) will cause exactly the kind of problems identified above.

So... the base stations in the 'lower 700 MHz band' in the USA will cause immense interference to the base stations in Mexico operating at the upper end of the Mexican 700 MHz band, and the base stations in Mexico will cause immense interference to the 'upper 700 MHz band' base stations in the USA.

There is no straightforward solution to this problem, other than one or other country adopting the same frequency plan as its neighbour. As both countries already have services operating in the bands, this is beyond unlikely. The only way to overcome such a problem is therefore to try and stop signals from one side of the border reaching the other side. The laws of physics dictate that the only way to do this is to build a barrier that is impervious to radio signals, such as, for example, a tall metallic wall (or one with metal running up the inside). Metal boxes known as Faraday cages are used in laboratories (and sci-fi movies) to perform just this task.

There is no straightforward solution to this problem, other than one or other country adopting the same frequency plan as its neighbour. As both countries already have services operating in the bands, this is beyond unlikely. The only way to overcome such a problem is therefore to try and stop signals from one side of the border reaching the other side. The laws of physics dictate that the only way to do this is to build a barrier that is impervious to radio signals, such as, for example, a tall metallic wall (or one with metal running up the inside). Metal boxes known as Faraday cages are used in laboratories (and sci-fi movies) to perform just this task.

The 700 MHz band was sold at auction in the USA for US$19 billion in 2008. Estimates of the cost of the wall vary, but the mean value is around US$20 billion. This is no co-incidence. Having paid US$19 billion for the spectrum in the 700 MHz band, the US operators have a reasonable expectation that they can use the frequencies without undue interference and thus a 'Faraday Wall' is necessary. As long as Mr Trump can build it for less than US$19 billion, the operators will be happy, and the Federal Reserve will still have made a small profit on the sale of the spectrum. Win-win as they say.

Wireless Waffle recently suggested that the high power short-wave transmissions coming from the HAARP site in Alaska were trying to trigger lightning strikes in an attempt to send radio signals strong enough to be received on a remote planet.

It seems that they are not the only ones who are generating very high power short-wave transmissions, but that the enormous dish at Arecibo in Puerto Rico has also been turned into a giant transmitter. Experiments taking place right now (from 24 to 31 July 2017) involve transmissions around either 5.125 or 8.175 MHz (the most recent transmissions have been on 5.095 MHz) with an effective radiated power of around 100 MW (MegaWatts).

It seems that they are not the only ones who are generating very high power short-wave transmissions, but that the enormous dish at Arecibo in Puerto Rico has also been turned into a giant transmitter. Experiments taking place right now (from 24 to 31 July 2017) involve transmissions around either 5.125 or 8.175 MHz (the most recent transmissions have been on 5.095 MHz) with an effective radiated power of around 100 MW (MegaWatts).

The purpose of the transmissions is to try and heat up the ionosphere for various experiments, including trying to establish Langmuir waves which excite oxygen atoms sufficiently that they emit light at visible wavelengths and light up the night sky in something known as 'airglow'. You couldn't make this stuff up!

Those strange lights in the night sky that you thought were UFOs... it's just scientists getting their oxygen atoms all excited. Nothing to worry about.

It seems that they are not the only ones who are generating very high power short-wave transmissions, but that the enormous dish at Arecibo in Puerto Rico has also been turned into a giant transmitter. Experiments taking place right now (from 24 to 31 July 2017) involve transmissions around either 5.125 or 8.175 MHz (the most recent transmissions have been on 5.095 MHz) with an effective radiated power of around 100 MW (MegaWatts).

It seems that they are not the only ones who are generating very high power short-wave transmissions, but that the enormous dish at Arecibo in Puerto Rico has also been turned into a giant transmitter. Experiments taking place right now (from 24 to 31 July 2017) involve transmissions around either 5.125 or 8.175 MHz (the most recent transmissions have been on 5.095 MHz) with an effective radiated power of around 100 MW (MegaWatts). The purpose of the transmissions is to try and heat up the ionosphere for various experiments, including trying to establish Langmuir waves which excite oxygen atoms sufficiently that they emit light at visible wavelengths and light up the night sky in something known as 'airglow'. You couldn't make this stuff up!

Those strange lights in the night sky that you thought were UFOs... it's just scientists getting their oxygen atoms all excited. Nothing to worry about.